Seizures

All contents of this resource were created for informational purposes only and are not intended to be a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, therapist, or other qualified health providers with any questions or concerns you may have.

Seizures are a significant concern in autism because of their high prevalence and association with increased mortality and morbidity among individuals with autism. Adding to this concern is that many symptoms of seizures look like the symptoms of autism, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. Therefore, if you suspect that seizures are causing any of your child’s autism-like behaviors, we strongly recommend you take them in for a comprehensive evaluation with a knowledgeable and experienced physician.

This article will help you navigate seizures in autism. In it, you will find the following information:

- Seizures vs. epilepsy

- Symptoms and types of seizures

- Seizures in autism (prevalence, concerns, diagnosing, causes, etc.)

- Treatment options

- Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs)

- Adverse effects of specific AEDs

- Pros and cons of non-AED treatments

- Emergency treatment options

Seizures and Epilepsy

Your brain consists of billions of nerve cells. It functions by sending electrical signals through these nerve cells. A seizure is the result of an abnormal electrical discharge between brain cells. Epilepsy is simply defined as having two seizures without an obvious trigger.

Seizures and epilepsy are fairly common in childhood. Many children experience febrile seizures when sick with a fever, and 1-2% of all children have a diagnosis of epilepsy. For most of these children, the seizures resolve within a year or two. However, a small percentage of children with epilepsy go on to have refractory epilepsy, which is difficult to control with anti-epileptic treatments.

Seizure Symptoms

Symptoms of seizures vary widely. While some episodes of seizure activity present no visible outward signs, others may manifest in one or more of the following ways:

- Staring spells

- Nausea/dizziness

- Loss of focus

- Disrupted sleep

- Rapid eye movements/blinking

- Involuntary body movements, such as muscle twitching or stiffening

- Unusual sensations (even visceral sensations, smells, tastes, or tingling)

- Loss of consciousness

- Complex behaviors

- Anxiousness or changes in mood

- Confusion or disorientation

Types of Seizures

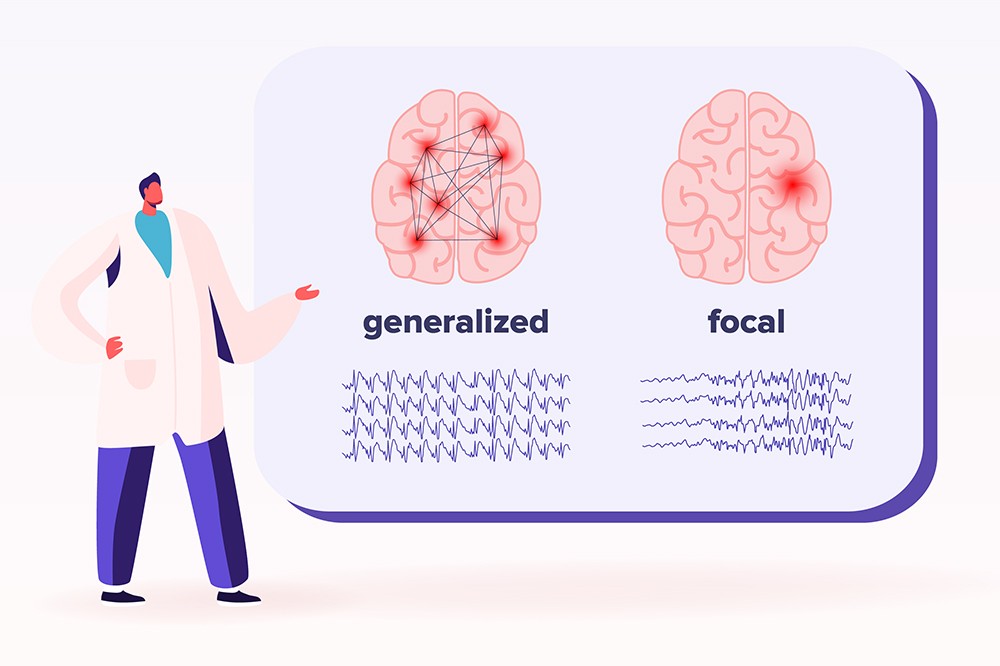

There are two broad types of seizures: generalized and focal (partial). Below is a brief description of each.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain. There are two types of generalized seizures:

- Absence seizures (petit mal): can cause a person to blink rapidly, stare out into space, or lose focus for a few seconds.

- Tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal): is one of the most severe types of clinical seizures where the entire brain can demonstrate abnormal electrical activity.

- When most people think of seizures, they think of generalized tonic-clonic seizures in which the whole body shakes rhythmically, and there is a loss of consciousness.

- While most tonic-clonic episodes last less than 5 minutes, they can be dangerous if they continue for 15 minutes or more.

Focal (Partial) Seizures

In focal (partial) seizures, only one part of the brain experiences abnormal electrical activity.

- Focal seizures can be very subtle, manifesting only as staring episodes or they might have no visible signs to indicate that a seizure is happening.

- Or, they can cause one part of the body, such as an arm or leg, to demonstrate rhythmic movement.

- Ultimately, how a focal seizure looks and feels depends on which area of the brain the seizure activity occurs because different parts of the brain are responsible for specific functions and sensations.

It is important to note that a seizure can begin as a focal seizure, in one part of the brain, and progress to a generalized seizure, affecting both sides of the brain.

Seizures in Autism

Seizures are relatively common among individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). While 1-2% of children in the general population develop epilepsy, the prevalence of epilepsy in ASD is much higher, with estimates varying from 5% to 38%.

Some individuals with ASD develop seizures in childhood, some at puberty, and some in adulthood. Although the prevalence of seizures by age is not well studied, recent studies suggest the risk remains high into adulthood.

It is noteworthy that specific subgroups within autism have a higher risk of developing seizures and epilepsy. Namely, individuals with comorbid intellectual disabilities, genetic abnormalities, and/or brain malformations.

The most concerning issue is the association between seizures with the increased mortality and morbidity among individuals with autism. For adults with autism, they are the leading cause of premature death.

Diagnosing Seizures in Autism

Seizures can be challenging to diagnose in autism. This is because overlapping symptoms (e.g., staring episodes, motor tics, and stereotyped movements) make it difficult to differentiate between the subtle signs of seizures and the characteristics of autism. Nevertheless, it is important to determine if these symptoms can be attributed to seizures or another neurological abnormality because they are treated very differently.

When it is unclear if a symptom is or isn’t being caused by a seizure, an extended, overnight, or 24-hour electroencephalogram (EEG) should be performed. Because EEGs provide a continuous recording of the brain’s electrical activity, they allow you to capture what is going on in the brain during suspicious behaviors.

Many doctors recommend a 24- to 48-hour EEG to gather needed information during both wakefulness and sleep. Ultimately, obtaining an extended EEG will increase your chance of getting a clear and accurate diagnosis.

Sub-Clinical Electrical Discharges

Individuals with ASD have a high rate of seizure-like activity when their brain waves are measured with an electroencephalogram. These are referred to as sub-clinical electrical discharges. The significance of these abnormalities is not clear as they rarely result in symptoms of seizure. However, some research studies associate them with cognitive dysfunction in children with epilepsy.

Furthermore, these seizure-like discharges are associated with specific epileptic syndromes that share characteristics with ASD, such as Landau-Kleffner Syndrome and Continuous Spike-wave Activity during Slow-wave Sleep.

Early research suggests that anti-epileptic medications may improve cognitive, behavioral, or psychiatric symptoms for individuals with sub-clinical discharges.

Causes of Seizures in Autism

Conditions that can trigger seizures in individuals (with or without ASD) include head injuries, infection or inflammation affecting the brain (e.g., encephalitis), ingestion or withdrawal from certain medications or recreational drugs, and disturbances of electrolyte levels.

Additionally, there is an association between specific genetic and metabolic syndromes and both ASD and seizures. For this reason, every child with ASD and seizures should have a comprehensive medical evaluation for known medical disorders that includes the following:

- A genetic workup, consisting of a chromosomal microarray, Fragile X, and Rett syndrome testing

- If these return normal, further testing may include an epilepsy genetic panel or whole exome genetic sequencing.

- Genetic testing for the following syndromes (if your child has certain dysmorphic features or characteristics):

- Tuberous Sclerosis Complex, Angelman, Prader–Willi, Velocardiofacial, and Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndromes

- Testing for Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cerebral Folate Deficiency, metabolic disorders with a high prevalence among individuals with ASD and seizures

- If supporting clinical characteristics exist, consider testing for other, much more rare metabolic disorders, such as:

- Succinic Semialdehyde Dehydrogenase Deficiency, Adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, Creatine Metabolism Disorder, Phenylketonuria, Pyridoxine dependent and responsive seizures, and Urea Cycle Disorders

- If supporting clinical characteristics exist, consider testing for other, much more rare metabolic disorders, such as:

Treatment Options for Seizures

Seizures are most commonly treated with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs), but non-AED treatments are also available. If a specific genetic or metabolic syndrome is associated with seizures in a child with ASD, there may be a specific treatment for that underlying condition. However, for the most part, AEDs are necessary to control seizures–even in children where an underlying genetic or metabolic disorder has been identified.

Below you will find information about AED, non-AED, and emergency treatment options for seizures.

Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs)

Although AEDs are first line for treating seizures, no AED has undergone evaluation for efficacy for the treatment of seizures in the ASD population. Recently, to determine whether specific treatments were more beneficial than others for individuals with ASD and seizures, 733 parents of children with ASD and seizures were asked to rate the effect of AEDs on seizures and other clinical factors including sleep, communication, behavior, attention and mood. The results of the ratings appear to confirm the clinical experience of many clinicians:

- Out of all AEDs examined, four provided the best seizure control and worsened other clinical factors the least:

- Valproate, Lamotrigine, Levetiracetam, and Ethosuximide

- Specifically, Valproate and Lamotrigine had the least detrimental effect on mood, and Lamotrigine appeared to have the least overall adverse effects.

Adverse Effects of Specific AEDs

When taking AEDs, it is common for individuals to experience one or more of the following:

- Neurological side-effects (i.e., ataxia, tremor, nystagmus)

- Behavioral side-effects (i.e., hyperactivity, agitation, aggressiveness)

- Gastrointestinal side-effects (i.e., abdominal pain, nausea)

- Some AEDs can cause an allergic reaction, which can be severe in some cases.

Specific adverse effects are highly dependent on the medication. Overall, newer AEDs, such as Lamotrigine, Oxcarbazepine, Topiramate, and Levetiracetam, have fewer serious adverse effects than older AEDs Phenobarbitol, Phenytoin, Primidone, and Carbamazepine. The exception to this is Valproate, an older anti-epileptic medication that appears to have good efficacy for many individuals with ASD. Still, Valproate does have some severe side effects (see more below).

In general, it is best to avoid older AEDs (Phenobarbitol, Phenytoin, Felbamate). They have a high incidence of cognitive and neurological adverse effects, which can exacerbate existing behavioral and cognitive abnormalities.

You can avoid serious side effects with careful monitoring. For this reason, it is best to have an experienced practitioner prescribe AED medications and monitor the patient. Particular care should be taken when using multiple AEDs as adverse effects can be cumulative. Since many AEDs elevate the risk of congenital disabilities, it is important to carefully consider the choice of AEDs in females of childbearing age.

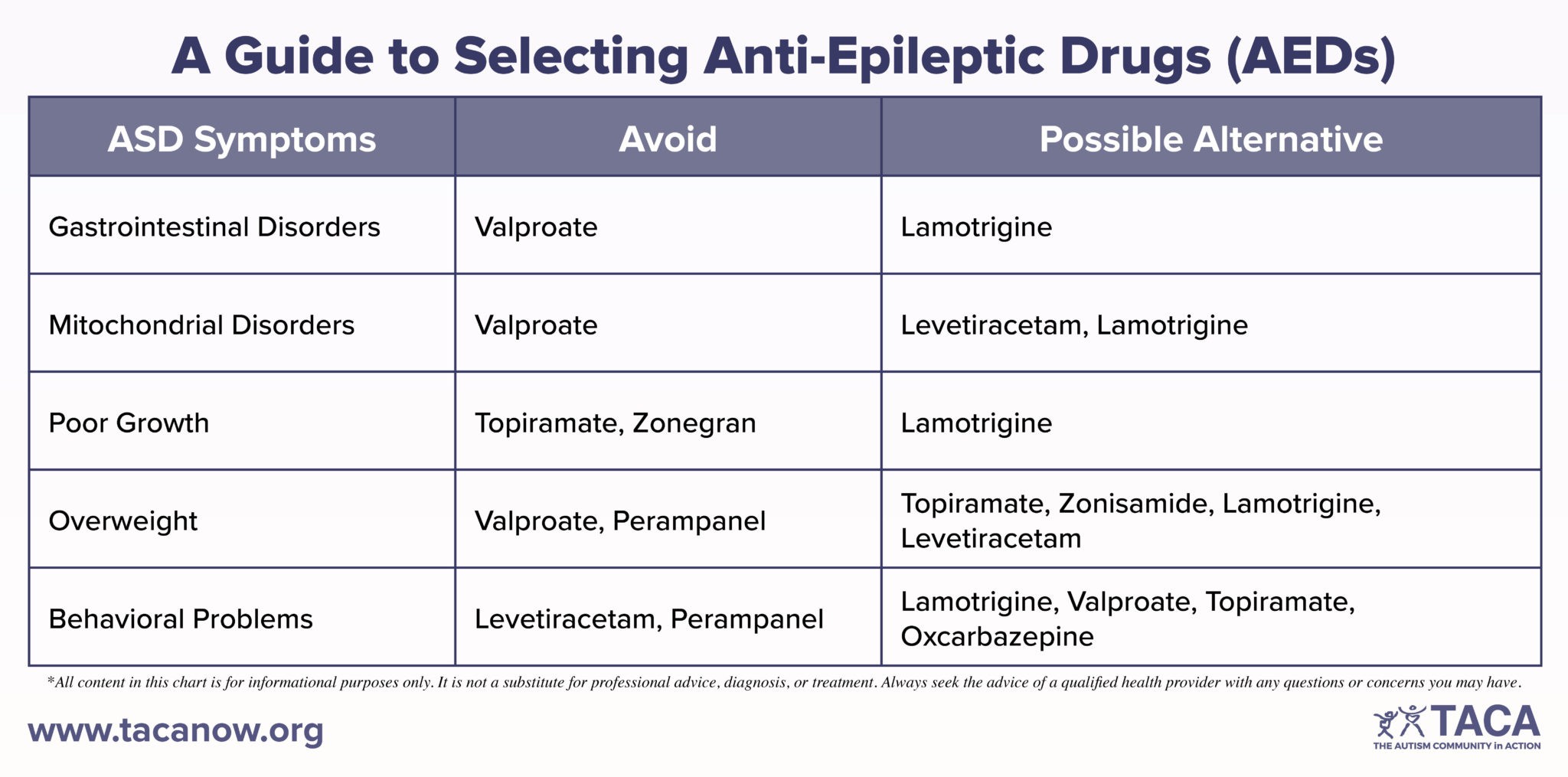

Below is a guide to selecting AEDs followed by information about the adverse effects of specific AEDs. Please note, adverse effect profiles have not been studied in ASD specifically, so it is unknown whether individuals with ASD have a higher incidence of adverse effects than other populations of individuals with epilepsy.

Lamotrigine (LAMICITAL)

- Lamotrigine has a low incidence of serious adverse effects and is generally well-tolerated.

- The most serious adverse effect of Lamotrigine is a life-threatening whole-body rash known as a Steven-Johnson’s reaction.

- You can reduce the risk of this occurring by increasing the Lamotrigine dose slowly towards the target dose.

Levetiracetam (KEPPRA)

- Levetiracetam has a low incidence of serious adverse effects and is probably one of the safest anti-epileptic drugs.

- The most prevalent adverse effects are behavioral, including agitation, aggressive behavior, and mood instability.

- Levetiracetam has been linked to suicide in a few individuals without ASD.

- In some cases, adding pyridoxine (vitamin B6) helps reduce adverse behavioral effects.

Valproate (DEPAKOTE)

- As mentioned above, Valproate is an older anti-epileptic medication that appears to have good efficacy for many individuals with ASD. Although Valproate can have serious side effects, you can take precautions to prevent them.

- Serious side effects include hepatotoxicity (liver toxicity), hyperammonemia (high ammonia), and pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas).

- Therefore, during the initial period of starting the medication, your child’s doctor must carefully monitor the toxicity of Valproate on the liver, pancreas, and blood cells.

- Complete blood count, liver function tests, amylase, and lipase during the initial period of starting the medication and if the patient experiences gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Once the doctor determines a stable dose, they will begin monitoring your child approximately every three months.

- L-carnitine may mitigate liver damage resulting from Valproate. Thus, co-treatment with L-carnitine is recommended.

- Therefore, during the initial period of starting the medication, your child’s doctor must carefully monitor the toxicity of Valproate on the liver, pancreas, and blood cells.

- Common adverse effects of Valproate include weight gain and thinning of the hair.

- The latter may respond to supplementation with selenium (10-20 mcg per day) and zinc (25-50 mg per day).

- Also, there is a link between long-term use of Valproate with bone loss, irregular menstruation, and polycystic ovary syndrome.

- The following should avoid Valproate:

- Individuals with certain mitochondrial disorders.

- Very young children – Hepatotoxicity may be more prevalent in children under two years of age.

- Also, children with Alpers syndrome – Valproate can be fatal to children with this disease resulting from the depletion of the mitochondrial DNA/ PolG-1 gene mutation.

- Women of childbearing age – there is evidence that prenatal exposure to the drug interferes greatly with concurrent fetal development.

Oxcarbazepine (TRILEPTAL)

- Hyponatremia (low blood sodium) can develop in some individuals when taking Trileptal.

Topiramate (TOPAMAX)

- Topiramate requires minimal metabolization by the liver and is excreted mostly unchanged by the kidney.

- Common adverse effects include weight loss and cognitive and psychomotor slowing.

- Topiramate can cause metabolic acidosis (high blood acid), nephrolithiasis (kidney stones), and oligohidrosis (decreased sweating).

- Because of this, individuals with kidney disorders should avoid Topiramate.

- Additionally, extra care during hot weather is necessary.

- Additionally, glaucoma (increased eye pressure) has occurred in rare cases, so you should take your child in for an evaluation if any vision symptoms arise.

- If possible, individuals with sulfa allergies should avoid Topiramate.

Zonisamde (ZONEGRAN)

- Zonisamide’s side effects are similar to the adverse effects of Topiramate (see above).

Clobazam (ONFI)

- Behavioral changes can often be seen in association with this medication.

- Additionally, Clobazam can cause excessive sleepiness.

- Therefore, take precautions when using other sedative drugs, especially in the benzodiazepine category.

- Furthermore, concurrent use with cannabidiol can lead to a buildup of a Clobazam byproduct, leading to excess sedation.

- Also, excessive drooling can occur.

Lacosamide (VIMPAT)

- Those with cardiac history should use Lacosamide with caution.

- This medication can lead to alterations in heart rhythm at higher doses, indicating the need for an EKG (electrocardiogram) in such cases.

Rufinamide (BANZEL)

- Adverse effects include headache and vomiting.

- Individuals with cardiac history should use Rufinamide with caution, as it can potentially alter heart rhythm.

- Higher doses of Rufinamide may require a need for an EKG (electrocardiogram).

- Also, individuals with sulfa allergies should avoid Rufinamide (if possible).

Cannabidiol (EPIDIOLEX)

- Cannabidiol (CBD) is available over-the-counter or by prescription as brand name Epidiolex.

- Gastrointestinal side effects, such as appetite change and diarrhea, are common.

- See above regarding concurrent usage with Clobazam.

Perampanel (FYCOMPA)

- Watch for increased aggressive behavior.

- In rare instances, there is an association with significant psychiatric disturbance and Perampanel.

- Additionally, weight gain is a common adverse effect of Perampanel.

Vigabatrin (SABRIL)

- There is an association between Vigabatrin with progressive and permanent visual loss.

- Thus, its use is typically restricted to controlling a particular type of seizure known as infantile spasms in a specific condition known as Tuberous Sclerosis.

Non-AED Options for Treating Seizures in Autism

When AEDs are not effective by themselves, parents may want to discuss alternative methods to treating seizures, such as special diets. Like AEDs, none of these treatments have undergone evaluation for efficacy in treating seizures within the ASD population.

A recent survey of 733 parents of children with ASD and seizures found that certain non-AED treatments improved sleep, communication, behavior, attention, and mood. The best treatments appear to be low-carbohydrate diets, such as the ketogenic, Atkin’s, or modified Atkin’s diets. These diets can also be effective in individuals without ASD who have epilepsy.

Below is an outline of information regarding several non-AED treatments.

Low Carbohydrate Diets

- Low carbohydrate diets, such as the ketogenic diet, have been very effective at controlling seizures in some children with refractory epilepsy.

- It is important to conduct any dietary treatment under a trained professional’s guidance, especially the ketogenic diet.

- The ketogenic diet can cause acidosis (high blood acid), so anyone on this diet needs careful monitoring.

- Because the ketogenic diet is very restrictive, some have tried the modified Atkins diet and found it effective.

- Another less restrictive diet to implement may be the low glycemic index diet, which emphasizes complex carbohydrates over simple carbohydrates.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

- Regular infusions of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) may help in cases of refractory epilepsy, where epileptic encephalopathy is the cause.

- Common adverse effects of IVIG include rash, headache, and fever and require prophylactic pretreatment.

- IVIG is contraindicated in individuals with kidney or heart problems and should be administered by a practitioner familiar with the treatment.

- Furthermore, some individuals develop increasingly severe allergic reactions to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. In such cases, changing the brand may reduce adverse effects.

Steroids

- In the course of treating epileptic encephalopathy or infantile spasms, treatment with high-dose steroids may help.

- While daily steroids may also be effective, they are difficult to maintain because of the high risk of adverse effects, including weight gain, edema, mood instability, and insomnia.

- Serious adverse effects include hypertension, immunosuppression, gastrointestinal ulceration, glucose instability, and osteoporosis. Therefore, doctors closely monitor anyone on steroids for extended periods.

- ACTH is a related medication with similar side effects.

Elimination Diets

- There are reports of isolated cases of improvement in seizures with the elimination of certain foods or preservatives. However, no extensive studies confirm this practice as effective.

- As mentioned above, it is essential to conduct any dietary treatment under a trained professional’s guidance.

Vagus Nerve Stimulator

- A vagus nerve stimulator is a small device implanted under the skin with a wire that wraps around the vagus nerve. The device stimulates the vagus nerve, which has neural inputs into the brain.

- It is believed that stimulation of the brain results in changes in several levels of neurotransmitters, particularly gamma-aminobutyric acid, which can help control seizures.

- Vagus nerve stimulators can cause alterations in vocalization, coughing, throat pain, and hoarseness.

- More serious side effects include spasms of the vocal cords, obstruction of the airway, and sleep apnea.

Corticectomy

- If seizures arise from one small area of the brain, it is possible for a neurosurgeon to remove the dysfunctional part of the brain.

- In order to determine if one portion of the brain is generating seizures, a patient must typically go through several extended hospitalizations.

- Because brain surgery can have serious adverse effects, doctors only suggest this option for most refractory patients.

- Similarly, guided laser therapy-related ablative procedures allow surgeons to remove dysfunctional portions of the brain without invasive surgery and minimal damage to surrounding structures.

Multiple Subpial Transection

- If a dysfunctional portion of the brain is found but cannot be removed, it is possible for a neurosurgeon to make small cuts in the brain areas surrounding the dysfunctional areas.

- Like a corticectomy, this requires brain surgery which can have serious adverse effects and requires an extended in-hospital workup.

- This particular therapy is not widely used, and there are only a few cases published to support its use.

Emergency Treatments

Individuals with epilepsy, especially those with frequent or prolonged seizures, should have an emergency medication readily available to stop any generalized seizure that occurs for 5 minutes or more.

The most common emergency medication is rectal Diazepam, which can cause drowsiness. Additionally, high doses or multiple doses of Diazepam can cause slow and ineffective breathing. Therefore, if it is necessary to use this medication, medical personnel should be called to evaluate the patient.

Newer, easy-to-use nasal spray devices are now available that administer either Midazolam or Diazepam to stop a seizure. Alternatively, some providers may prescribe Clonazepam dissolvable oral tablets as a rescue medication.

Additional Resources with Information About Seizures and Epilepsy

- The Epilepsy Foundation of America

- Autism Research Institute

- AAP recommends genetic testing, metabolic testing, EEG, neuroimaging, specialist workup

- American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommends whole exome genetic testing as a first-line test for developmental delay, intellectual disability, epilepsy, or autism spectrum disorder.

- Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Abnormalities of Clinical EEG: A Qualitative Review

- Summary states all autism needs 24hr + EEG

- Get Genetic Testing: Up to 70% of epilepsy cases are caused by genetic factors